Duignans of Wellington

The Duignan’s of Wellington, New Zealand are decended from a long line of Duignan’s who built and lived around Kilronan Abbey County Leitrim, Ireland.

The Duignans, originally Ó Duibhgeannáin, were a distinguished bardic and historical family in medieval and early modern Ireland. As part of the learned class, they served as hereditary historians (seanchaí), scribes, and poets to Gaelic nobility, particularly in the regions of Leitrim, Longford, and Roscommon. The Duignans played a key role in preserving and transcribing important annals and bardic poetry, contributing to the continuity of Ireland’s oral and written tradition. Even as the Gaelic order declined in the 17th century, they continued to produce copy manuscripts, marking the family as one of the last bastions of native Irish scholarship. Our role as a family over the centuries is reflected in our family crest. The inscription Stair Maistreas na Beatha is Irish for “History is the Mistress (or Teacher) of Life.” It reminds us that we learn not just through books, but by doing—by building. When the Duignan family built Kilronan Abbey and its school of learning in the 1300s, they didn’t only get their hands dirty building. The walls they built still stand over 700 years later, a testament to hands-on dedication. But their work didn’t stop only with building. Within the protection of those well built walls, they then build something else—ideas. Through scholarship, writing, and storytelling, they created a world of thought for their times and the future. Next is a young person’s version of the Duignan story and below that is the genealogy that leads to our family’s story at Kilronan Abbey.

The Duignan’s at Kilronan Abbey

The Duignans were famous in Christian Ireland as scholars, writers, bards and poets. Their job was to keep stories, law and history safe—just like librarians, teachers, writers, scholars, playwrights, film makers, and song-writers all rolled into one. Some people even whisper that, long before churches, their ancestors did a similar job for the old Druid schools, guarding wisdom beside sacred oaks.

Long ago in the 1300s, the Duignans built their own abbey beside the sparkling waters of Lough Meelagh, near the quiet village of Keadue in what is now County Roscommon. With strong hands and carefully made tools, they raised stone walls where once there had only been trees and grass. They even used an old carefully made doorway from an earlier church, so that the past could walk through into the future. This new place—Kilronan Abbey—was not just for meditation and prayers, but for also for learning, reading, and keeping Ireland’s stories safe.

What was life like at Kilronan Abbey in those days so long ago? Well, at dawn a girl and her brother might wake, rub their eyes and get up from their straw beds in the timber barn. Then they would hurry to the to the kitchen and on to the abbey door with fresh bread and warm milk for the scribes.

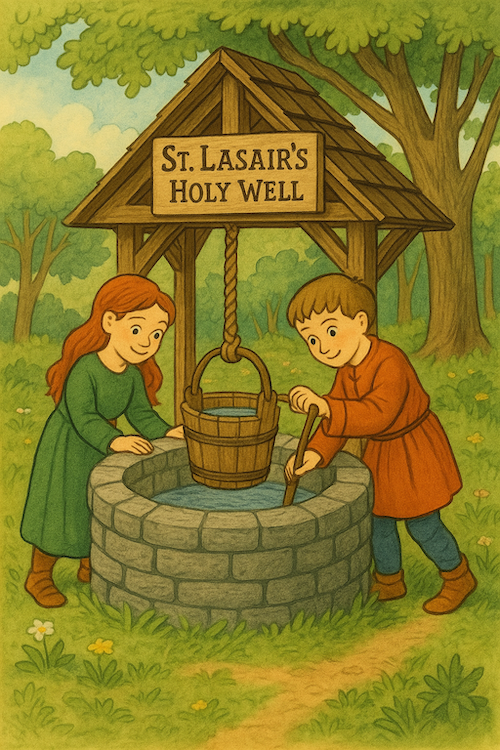

They would fetch water from St Lasair’s Holy Well under the ash trees and carry it back to the abbey. St. Lasair was the daughter of St. Ronan whom Kilronan is named after. People come to her well to mediated and pray because they want to be healed from hurts or sicknesses or sadness. It is said that St. Lansair one day came upon an injured soldier, she picked up some clay beneath a cliff and blessed it and put it on his wounds. After that it is said that he was healed. From then on people would take some clay from near this place and carry it with them as a symbol of St. Lasair’s care and concern, Just coming there can still help people feel better because they can remember St. Lasair and that she was a good person. She cared for others and she would care for them if she was here now with them. And as they meditate they like to let themselves feel that she is still somehow in that place looking down on them and smiling. The children would stop and think for a moment about St. lasair and then get on with their chores of getting water each day and going back and sweeping the flagstone floor of the abbey. After their chores they would go to look in at the door of the writing room. They loved smelling the soft smell of the ink, watch the candles flicker and hear the tiny scratches of goose quill pens as the scholars wrote their books in silence.

If the ollamh (chief scholar) noticed them at the door they would tap their quill on the desk and the children were allowed to come in. They might practise drawing the twisting first letter of a Saint Ronan’s name, or hand something to one of the scholars. They would look at the beautiful illuminated manuscripts with wonderful pictures to go with the stories that were being written. It was a silent place where whispering was allowed only for Latin prayers or tricky Irish spellings. The scholars recorded the history of the times and wrote about philosophy and theology—it is about the reasons why things are the way they are in the world and how people can be good people as they live their lives.

By late morning the quills paused and the children were let loose. Out on the sunny pasture they chased hares and rabbits with little slings. If they were lucky, a plump rabbit became supper; if not, they still returned with wild sorrel and berries from the hedges. Sometimes on hot days they would swim in the cool waters of lough (lake) Meelagh which is near Kilronan Abbey.

Some afternoons a travelling bard arrived, harp tucked under her cloak . She would sit on a mossy stone and sing of Cú Chulainn or of gentle St Ronan who first blessed the land here. The boy beat time on a drum-skin, the girl hummed along, and the monks smiled to hear their own words carried on new voices.

They knew every corner of the abbey grounds: the yew that shaded St Ronan’s Well, the ivy arch where swallows nested, and the rounded boulder said to mark the saint’s footprint. Lough Meelagh, silver and still, mirrored the sky; at dusk you could almost believe ancient druids still whispered across its surface.

As the sun slipped behind the Arigna hills, orange light spilled through the abbey’s Gothic windows. Inside, candles flickered while the scholars dotted i’s and crossed long Gaelic s’s in the books they were writing.

After supper of oat-cakes, rabbit stew and sweet well-water, the youngsters dozed on straw pallets, dreaming of the day they, too, would copy golden letters or roam Ireland as harpers. The hum of crickets and the soft rustle of vellum pages turned by moon-watching monks lulled them to sleep.

Because the Duignan children and their elders kept building and writing, Ireland’s stories survived wars, fires and the long march of time. Every notebook you fill, every song you sing, follows the path they began— it still applies today that buildings built and words written, can grow for a thousand years.

Concept, story line, direction and editing by Paul Duignan, initial drafting and images created by ChatGPT o3 2025.

Pictures from Today

Kilronan Abbey

Sources: https://www.megalithicireland.com/Kilronan%20Abbey%2C%20Roscommon.html

St. Lasair’s Holy Well

Source: https://www.megalithicireland.com/St%20Lassair%27s%20Holy%20Well%2C%20Kilronan.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Lough (lake) Meelagh

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lough_Meelagh

Arigna Hills

Source: https://pixabay.com/photos/arigna-mist-mountains-sky-nature-8413584/

David O’Duibgeannain’s writing

David was a scholar who would have worked at Kilronan Abbey in the 1600’s. This is his writing. In the margin of one of his manuscripts he wrote: ‘It’s a pity, o little white book, the day will come, for sure when over your page it will be said, the hand that wrote it is dead’. We should remember David and his work recording the history of and thought of his times so that we can read it now.

Source: The Book of the Duignans which Paul Duignan has from a shource in Ireland.

Our Geneology

(Created after a discussion with ChatGPT o3 2025, so would need to be checked, this is the family line that leads to the family seat at Kilronan Abbey from the 4th Century through to the 17th Century. We know that the Wellington Duignan’s came from Kilronan to New Zealand in the 1880’s).

1. Niall Noígíallach (“Niall of the Nine Hostages”) – d. c. 405

2. Maine of Tethba

3. Fiachna

4. Éanna

5. Crimthann

6. Brian

7. Bracan

8. Breanainn

9. Crimthann (II)

10. Connhach

11. Aodh

12. Corc

13. Cathasach

14. Blathmac

15. Aodh (II)

16. Conghall

17. Colla

18. Conaig

19. Conghalach

20. Murchadh

21. Muirchertaigh

22. Diarmaid

23. Conchobair

24. Breasal

25. Braighte

26. Gabhalach

27. Maol

28. Beannachta

29. Fionnachta

30. Tadhgan

31. Maol Odhair

32. Cearnachan

33. Duibhgeann ← eponym of the surname Ó Duibhgeannáin / Duignan

34. Naomhtuc mac Duibhgeannáin (fl. late 12th c.)

35. Pilip na hInnise (“Philip of the Island”)

36. Poil an Fhíona (“Paul of the Wine”)

37. Lucais Ancaire (“Lucas the Anchorite”)

38. Fearghall Muimhneach Ó Duibhgeannáin †1347 — rebuilder & erenagh of Kilronan Abbey

39. Matha Ghlais

40. Maoileachlainn

41. Dubhthaigh Mór †1511 — ollamh of Conmaicne

42. Dubhthaigh Óg †1578 — last recorded ollamh of Conmaicne

43. Duilbh (fl. c. 1580–1610)

44. Maolmhuire (early 17th c.)

45. Matthew Glas

46. Daibhidh Bacach Ó Duibhgeannáin (fl. 1651–1696) — itinerant scribe & poet